Thoughts about Herbie Hancock on his birthday

Learning from his younger friend and colleague, Tony Williams (1945-1997)

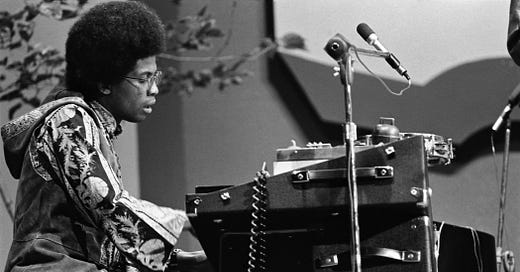

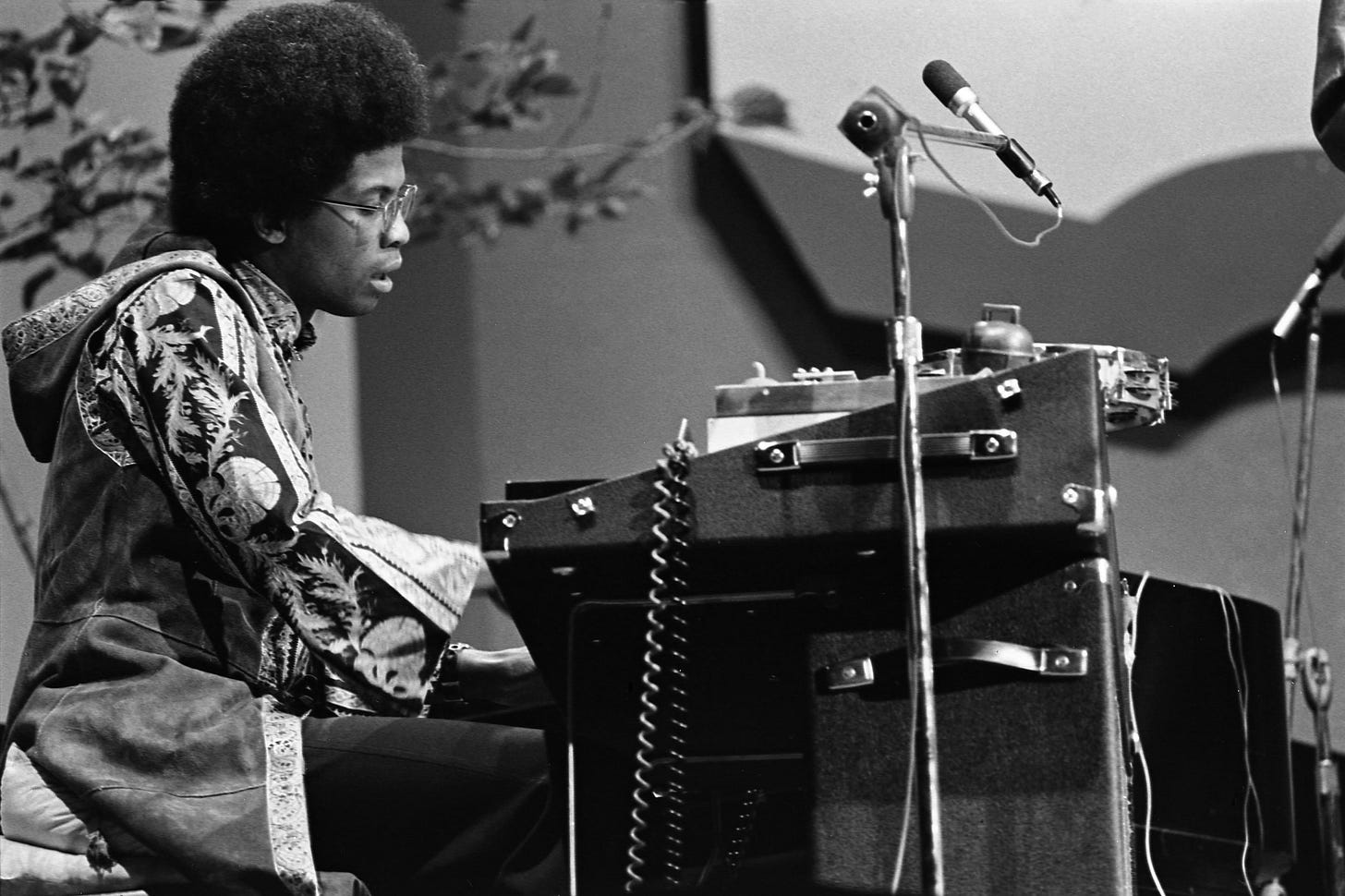

Photo credit: Veryl Oakland. Herbie Hancock in 1971, from Bob Gluck, You’ll Know When You Get There: Herbie Hancock and the Mwandishi Band

April 21st is Herbie Hancock’s birthday. Having written about his music a fair bit in the past, I’ve been pondering what I could add on his recent 85th birthday.

What struck me as I began to write is the deep relationship Hancock built with drummer Tony Williams. This began in 1963, shortly before they each joined the Miles Davis Quintet. I’ve experienced enormous joy listening to how the two interacted musically, particularly during their final year with Miles Davis. An assignment I regularly gave my university students was to listen in great detail to brief examples of their interplay and how it intersected with Ron Carter, particularly during Wayne Shorter’s solos.

Today, I find myself thinking again about the early stages of their connection and, in particularly, what Hancock learned from his younger colleague and friend.

When I first spoke with Herbie Hancock in 2008, I asked him to talk about how they met.

“Tony had been working with Sam Rivers in Boston when I first met him, [although] I didn’t hear him. At that time, he was sixteen. And it’s funny: I went to Boston [playing] with Eric Dolphy, and they had some kind of banner in the club [where we were performing] - a club called Connolly’s – [which said] ‘Jackie McLean with the young Tony Williams on drums,’ or something like that. I met Tony during that time I was in Boston with Eric, but I didn’t hear him play. So that was probably in November of ’62. The next month, December, Tony had a birthday; he turned seventeen (laugher). And then two months later, in February of ’63, he moved to New York.”

Screenshot from BBC video of Tony Williams playing with Herbie Hancock, 1991.

Herbie Hancock had also played with Dolphy. For Hancock, Dolphy offered an early exposure to newer ideas that were emerging within jazz:

“I hadn’t paid that much attention to the avant-garde scene. It was a curiosity that I had. But I wasn’t curious enough to really actively pursue finding out about it. But then I got a call from Eric Dolphy to do a little tour with him. And so, I took the gig because, first of all, it was an opportunity to find out something about the avant-garde.”

Hancock didn’t know quite what to expect, but he was relieved to discover that Dolphy’s music

“did have chords. But I had thought beforehand: ‘obviously, it doesn’t sound like the more typical chordal approach.’ I said to myself: ‘I wonder, if I broke some of the rules I normally use for playing, could that lead me to a doorway for some out playing?’ (laughs) That’s what I decided to try, and it seemed to work. [And for me], that was like an entry point.”

That “entry point” was not the first juncture point in Hancock’s musical development. As he explained in an interview with Julie Coryell, jazz made little sense to him in his fourth year as a pianist. Mind you, he was 11 at the time.

“… anytime I heard it on the radio, I would usually turn it off because I couldn’t make heads or tails out of it... The chords sounded like they were off the moon…”

Three years later and in his second year of high school (at age 14), Hancock’s perspective shifted after he heard a pianist who was only slightly older:

“… again it sounded like music off the moon, but it was cohesive… [and] made that kind of sense, although I had no idea what they were playing.”

Like his peers at Hyde Park High in Chicago, most of them white, Hancock was listening to pianists George Shearing and Erroll Garner, but his next discovery came on his own - the musical world of Art Blakey, Horace Silver, and Max Roach – musicians who were bringing a rhythm and blues and gospel inflection to jazz. In this way, they bridged the music emerging from bebop with music that had broad popularity in Black communities. Blakey and Silver, in particular, were musicians that the other high school students had dismissed.

Several years later, as a 20-year-old college graduate, Hancock began to build a musical career in Chicago. Due to a snowstorm that stranded trumpeter Donald Byrd’s bandmates, Hancock was asked to join Byrd’s rhythm section. Clearly that weekend’s pairing went well, and Byrd invited Hancock to move to New York and join his band. This was in 1961.

Two years later, Tony Williams also moved to New York. Drummer Max Roach, an older generation pioneer recalled in a 1997 JazzTimes interview (shortly after Williams’ death):

“[Tony’s] mother gave him permission to come down and visit me [in New York] one summer. His mother was a friend of Abbey [Lincoln]’s, and I was married to Abbey at the time. He stayed in our place. He was about 15 or so. We went out to a session one night, and Jackie McLean heard him...”

Photo from Tony Williams Official Facebook Page, date unknown, maybe late 1980s.

McLean soon suggested that Williams should move to New York City and, as had happened with Herbie Hancock, Williams was hired to join the ensemble of a well-known band leader. Hancock narrates:

“Sometime around then he [Tony Williams] called me, because I had given him my number. He said that he had moved to New York. Inside my head I’m thinking: ‘This kid from Boston is calling.’ So, I politely blew him off. He was nice; he wasn’t a pest or anything, so I wasn’t rude to him. I figured the best he could play was good for someone who was seventeen.

“A couple months later, I got a gig with Jackie McLean and I asked Jackie who was playing in the band and among the people were Eddie Kahn on bass and Tony Williams on drums. I said: ‘Tony? That little kid from Boston?” He said: “Yeah.’ I said: ‘Look, Jackie, can he really play drums, or is he like, really good for a seventeen-year-old drummer?’ He said: ‘Herbie, why don’t you do this – why don’t you come down to the gig and hear for yourself, come to your own conclusion.’ I said: ‘Ok, I’ll do that.’

“Well, we played a club called the Blue Coronet. It was maybe a sound check rehearsal. At the first [moment], Jackie ticked the tune off, to where it first hit, on the downbeat, Tony played some stuff, I had to stop playing. (laughter) It blew my mind so bad. You know, I was absolutely amazed. So, I had a great time at that gig. Then after that, I was the one calling Tony, I said ‘Hey man, what’s happening?’ So, it was like I was the little kid! (laughs) I wanted to find out from him what was going on.”

Indeed, even at age 16 and 17, Tony Williams had a lot to teach Herbie Hancock who, mind you, was less than five years older than the drummer.

Tony Williams was raised in Boston. His father was a saxophonist; by the time Tony began formal drum study at age 11, this gained him entre to the City’s clubs. Within three years, Williams was playing with Sam Rivers, a masterful but under-sung, exploratory saxophonist and composer. Among Rivers’ ideas was to play sessions in art galleries; the paintings would serve as seeds for collective improvisation. Tony Williams participated in sessions like these, and as Williams described to Pat Cox in 1970: “we'd have an ensemble on Sundays and the guys would improvise to a time watch, to numbers, on the wall.”

Rivers was very much tuned into the contemporaneous avant-garde, including the music of John Cage, as well as new trends in jazz. This was information he conveyed to Tony Williams. Williams, in turn, taught Herbie Hancock much of what he had learned. They came to share a fascination with new ideas and technologies.

In New York, Hancock and Williams each joined the cadre of musicians playing in sessions recorded by the Blue Note label, and of course in 1963, they became members of the Miles Davis Quintet.

Photo credit: Jan Persson, from Bob Gluck, The Miles Davis Lost Quintet and Other Revolutionary Ensembles

Hancock and Williams also released first albums of their own on Blue Note.

The first of these were Hancock’s Takin' Off (1962), My Point of View (1963), Inventions and Dimensions (1963), Empyrian Isles (1964), and Maiden Voyage (1965) - and Williams’ Life Time (1964) and Spring (1965). During this period, Williams was also playing and conversing with Cecil Taylor.

Williams invited Hancock to play on each of his albums. The way Williams conveyed his musical ideas in part reflected concepts and techniques learned from Sam Rivers. Hancock describd this as

“[not] in terms of notes or chords but . . . a bit like we could address the making of a painting, in terms of shapes, colors” and, maybe less directly spoken, in emotional qualities and levels and intensities of energy. Hancock summarized his experience to Len Lyons:

“From Tony Williams I learned so much about cross rhythms, about Indian rhythms. I got turned on to avant-garde jazz, say, from Coltrane on, through Tony, who was listening to that stuff carefully. That was his thing. He helped me get beyond hearing it as funny notes and really appreciating it like a piece of sculpture. He also turned me on to a lot of contemporary classical music. Tony and I used to hang out together. He was probably my closest friend then, and he was only seventeen. I was twenty-three, practically an old man.”

Hancock’s musical horizons were rapidly expanding. In 1964, Hancock told John Mehegan that he and Williams were gaining an interest in the experimental electronic music of the day:

“I first heard electronic music about a year ago and now I am beginning to ‘hear’ or relate to it in some sense. Tony Williams and I are going to buy an oscilloscope and tape apparatus and start fooling around with it.”

An ARP synthesizer advertisement from, I believe, Contemporary Keyboard magazine, many years later

More broadly, Hancock’s musical conception was broadening, and this influenced the evolution of the Miles Davis Quintet and subsequently, Hancock’s first Sextet and the Mwandishi Band of 1970-1973.

Screenshot from INA French TV segment of Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi Band, 1971.

I close with a further quotation from a 24-year old Herbie Hancock, speaking to John Mehegan.

“Any form of organized sound can be thought of as music and this entire field must be known to the modern musicians… I think that listening to various kinds of organized sound can broaden the scope of the jazz musician so that we are aware how sounds can be used. Also, rhythms, dynamics and timbres of our individual instruments. For instance, I have been fooling around with the wires, the sounding board and the pedals on the piano and I have been listening to the sounds, not only of the instrument, but the entire physical components of the piano. For instance, my telephone bell can be made to vibrate on my piano by striking the pedals.”

Herbie Hancock has always had a broad imagination and tremendous curiosity about new things to learn. Yet the role of Tony Williams in this learning process shouldn’t be lost.

In important ways Williams, “that little kid from Boston” had become the teacher from whom Herbie Hancock “wanted to find out from him what was going on.”

Happy birthday, Herbie Hancock!

Sources:

Julie Coryell and Laura Friedman, Jazz-rock fusion, the people, the music. Dell Publishing, 1978 / Hal Leonard, 2000. Interview with Herbie Hancock.

Pat Cox, “Tony Williams: An Interview Scenario.” Down Beat, May 28, 1970.

Bob Gluck, interview with Herbie Hancock, December 19, 2008.

Bob Gluck, You’ll Know When You Get There, Herbie Hancock and the Mwandishi Band. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Len Lyons, The Great Jazz Pianists. William Morrow, 1983. Interview with Herbie Hancock.

John Mehegan, “Discussion – Herbie Hancock Talks to John Mehegan.” Jazz 3:5, September 1964.

Greg Robinson, “Max Roach Remembers Tony Williams. JazzTimes, June 1, 1997. Updated June 2024 version.