Paul Winter and how musical experience can be a path towards caring about other species

How my exploration of Paul Winter's music led to my writing a book about his ideas, "The Musical World of Paul Winter" (Terra Nova, 2025)

You may know of Paul Winter’s music or his efforts to celebrate and protect whales, wolves, and other species. You may be familiar with his annual Winter Solstice Celebrations in New York City and more recently, across New England. Maybe his name is unfamiliar to you.

I enjoy writing about musicians whose ideas are innovative. This is why Ornette Coleman has figured so heavily in my work. Coleman’s “harmolodic” concept suggested a new balance between autonomy and collectivity when musicians play together. Think of this as a group conversation in which participants are discussing a topic about which each individual has their own distinct or even differing opinion, and they are expressing it to varying degrees at the same time. Most people would agree that Coleman’s ideas were revolutionary. But what makes Paul Winter’s musical ideas unique, also on a high level?

Paul Winter has been on my radar since the early 1970s. His concept for a band was drawn from the Elizabethan era “Consort,” an intimate group that played “diverse music.” He expanded its existing improvisatory spirit and greatly broadened the meaning of the term “diverse’. In Winter’s case, the music came to span Brazilian samba and Charles Ives, Johann Sebastian Bach and African American spirituals.

The Consort of the early 70s was free-spirited, virtuosic, and alternately contemplative or intense. Musical values from his 1960s jazz sextet were paired with a more informal, less tradition-bound, collage-like sensibility. It was not (yet) common to combine the sounds of a soprano saxophone with sitar and tabla, bass clarinet and classical guitar. Something about him - and the musicians that he chose to play with - caught me.

I experienced Paul Winter’s Consort of the late 1970s-1980s as a musical sea change. His aesthetics had shifted when I saw a new Consort perform in 1978-79 at Carnegie Hall and at the Clearwater Festival by New York State’s Hudson River. The music now conveyed a distinct message coursing through its circular melodies, Brazilian rhythms, the glorious singing of Susan Osborn… and recorded animal voices.

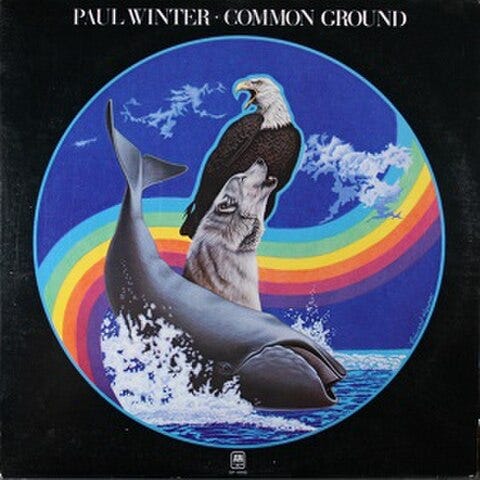

Winter’s conception was visible in the cover art to his 1978 album Common Ground. In the foreground we see a humpback whale, wolf and eagle, each separate yet woven together by a multicolor rainbow floating in the sky, the choppy sea below. The imagery was framed within a sky-blue globe. Each animal dwelled within its distinct habitat, yet all three were juxtaposed. Winter’s message: we share a living planet with a diversity of other species. Human interdependence extends beyond humanity to the multitude of living beings. The earth itself is a living being.

Paul Winter sought to sonically convey the idea that humans can perceive and find meaning in the voices of species very different from our own. He achieved this by including the sounds of wolves and humpback whales within his musical vocabulary, and by composing saxophone melodies that organically emerge from those voices. Enduring examples include “Wolf Eyes” (set to harmonies by David Darling) and “Ocean Dream” from Common Ground, and “Lullaby from the Great Mother Whale for the Baby Seal Pups” on Callings (1980, richly harmonized by Jim Scott).

Listen to "Wolf Eyes" on Paul Winter's BandCamp page

Listen to "Lullaby from the Great Mother Whale..." on Paul wiinter's BandCamp page

A dramatic highlight of Consort concerts came when audience members were invited to join in what Winter called a “howl’elujah chorus.” This practice continues have a place in Paul Winter’s concerts. Winter adapted a ritual from Canadian national parks to encourage a felt connection with wolves. In Winter’s hands, the collective howling reflected his affirmation that the Consort, its audience, and wolf calls all together represent a global village. Winter later called this new music that celebrated the earth and all its creatures “earth music.” The term also reflected some of the locations within nature - such as the Grand Canyon - where the Paul Winter Consort recorded

Watch a video clip from a 2014 concert in South Dakota: Paul Winter "Howlelujiah Chorus" for Leonard Peltier & the Black Hills

Paul Winter’s idea - to build human connection to animals through music - arose from personal experience. At a lecture by scientist Roger Payne in 1969, he first heard recordings of a humpback whale, sounds in which he perceived qualities shared with human music. This led him to:

“realize that there is perhaps a universal yearning that is shared by all species, this calling, crying quality in their singing and awakened me to the crisis of what we're doing to the Earth in a way that I had not been aware before.”

A decade later, following a whale watching and music making trip to Baja California, Winter heard about a slaughter of harp seals. While

“…listening to a recording of a long humpback whale song, I found this melody which sounded like a lullaby… I had this fantasy, that this song, from one of the largest mammals in the sea, was crying out for the fate of these small, helpless creatures. It was an act of reverence to put these humble human harmonies beneath this whale melody.”

That humans could endanger species - through hunting and environmental degradation - struck a chord within Winter, providing a clarity about his life’s work.

Winter’s musical innovation does share a commonality with Ornette Coleman’s – the message is embodied within the music itself. Where that idea took each of them differed.

For Winter, interweaving sounds of other species within his own music narrowed the separation that humans perceive between themselves and those creatures. The participatory “howl’elujah chorus” shared the same goal. Beautiful melodies and harmonies, already a strongly felt musical value for Winter, became a central feature of the way he felt his music could become a means to engaging listeners through their emotions. Just as he had experienced feelings of empathy for the humpback whale and baby seals, so could others.

What Paul Winter decided upon was a simultaneously musical and messaging concept: rather than admonishing people to think ecologically, seek to lead them towards caring about the planet by compassionately capturing human emotions. Do so by drawing upon the musical qualities of animal voices as material humans can perceive as musical.

Given the urgency of environmental crisis, one can argue in favor of other strategies in support of the environment or, ideally, choose more than one. But this musical approach was Paul Winter’s unique contribution. It also provided an answer to a question many artists ask: how can one make a meaningful contribution through one’s music, beyond aesthetic appreciation and entertainment.

Again, Paul Winter’s core idea:

Embody one’s message within the music itself.

Since the message is the inherent value of endangered species and the planet, incorporate sounds of those species within a musical pallet that includes melodies based upon those sounds.

Do so in a way that emotionally engages listeners.

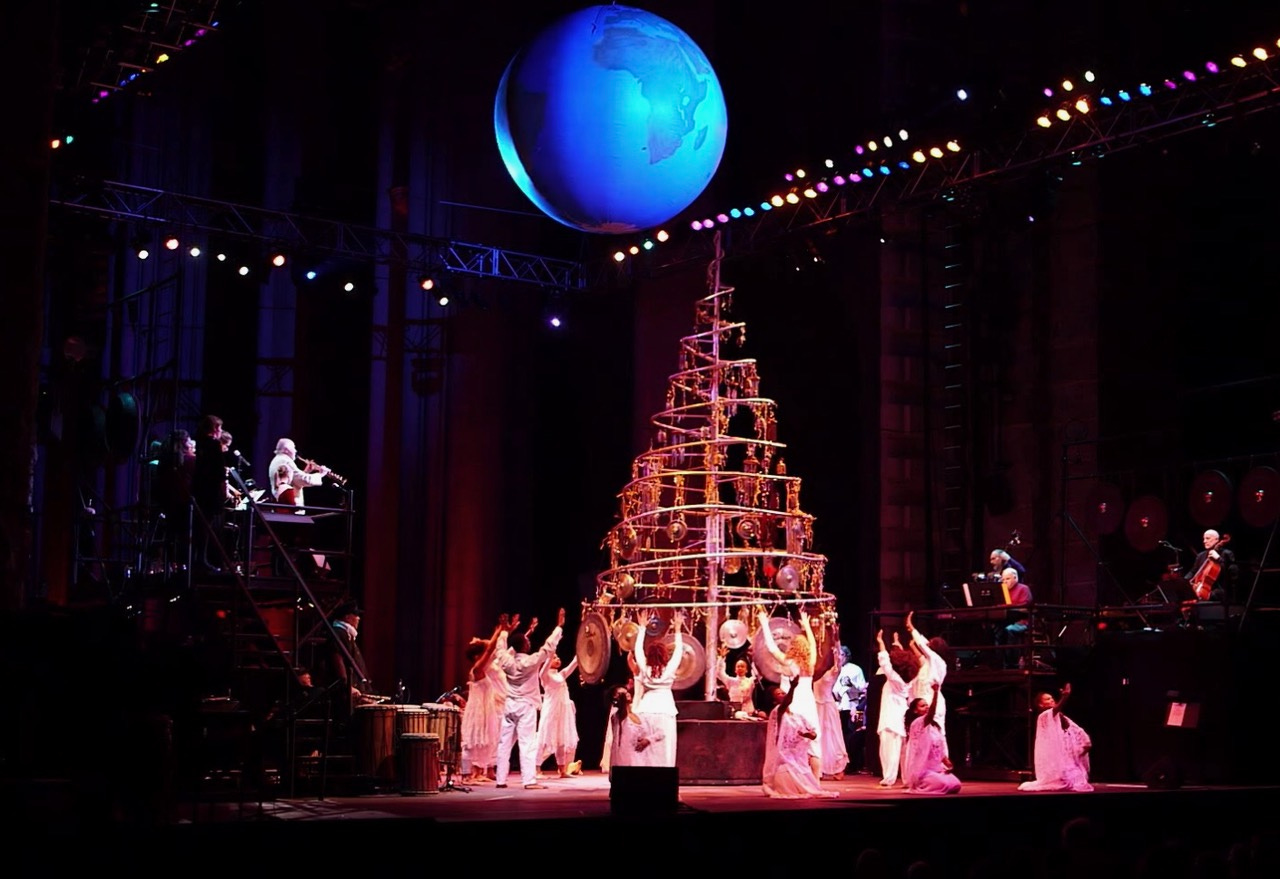

Create larger than life events, such as “Paul Winter’s Winter Solstice Celebration” that allow people to head home feeling good about their potential to translate their feelings into action.

Photo by Joel Chadabe, rehearsal for Winter Solstice Celebration 2018

Writing this book allowed me the pleasure of re-listening to decades of Paul Winter’s music, converse with Consort members who had personally taught me over the decades, and ponder how Winter’s musical ideas evolved. I’ve appreciated Winter’s warmth and the concerted efforts of the late Joel Chadabe who publishing a prototype manuscript that set the stage for the full edition now published by David Rothenberg on Terra Nova Editions.

For more information about my book, The Musical World of Paul Winter (2025): https://www.terranovapress.com/books/musical-world-of-paul-winter

Note: I explore Ornette Coleman’s ideas in some detail within two of my books, The Miles Davis Lost Quintet and Other Revolutionary Ensembles” (1976) and Pat Metheny, Stories beyond Words (2024), both from University of Chicago Press. For information about these and You’ll Know When You Get There: Herbie Hancock and the Mwandishi Band (2012): https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/author/G/B/au10327525.html

I just learned of you and your writings through Jim Scott's Facebook stream last night. Thanks for writing about one of most personally influential musicians and ensembles during my lifetime. I've purchased the Kindle version and look forward to the exploration.